The Incredible Shrinking Russia

As if on cue, as if waiting for me to bring up Russia’s World Cup difficulties, a new development reared its head over the holidays. On Christmas Eve, the Associated Press reported that the entire 16-club contingent in the Russian Premier League will be asking their players to accept a substantial pay cut.

As part of the international condemnation of Russia’s advances on Ukraine, economic sanctions have come from the United States, Canada, EU, Japan, Australia and New Zealand, which were in turn met with retaliatory sanctions from Russia which, in effect, have only served to exacerbate the intended sanctions. There’s a Wikipedia page listing them off, because there is a Wikipedia page for just about everything. There are travel bans, trade bans, transactions bans, asset freezes, suspensions of talks regarding other issues of proposed cooperation, and one of Russia’s retaliatory sanctions bans the import of food from the sanctioning countries. This, collectively, has caused the Russian economy to tank to the point that singular American companies are worth more than the entire Russian stock market.

Sometimes people get to thinking that the stratified salaries of sports stars are in utter disconnect with the society around them. But the salaries can only be what someone is able to pay. And even the biggest soccer clubs aren’t really THAT valuable in the grand scheme of things. In May, Forbes listed the most valuable clubs on the planet, and top-ranked Real Madrid came out as being worth $3.44 billion, with FC Barcelona, Manchester United, Bayern Munich and Arsenal also topping the billion-dollar mark. The bottom-ranked company on the 2014 Fortune 1000- not 500, but 1000– is Magellan Midstream Partners, based out of Tulsa. They deal in oil pipelines. Odds are you have never heard of them before; I certainly haven’t. Their market cap on March 31 was $15.8 billion, also known as over 4 1/2 Real Madrids.

It’s nice to own a sports team, but ultimately, you probably have more important things to do in order to have the money it takes to own a sports team. And Russian soccer club owners have some important things on their minds, such as the steep decline in value of their domestic currency. Eventually, the pain gets passed to the players.

Which you’d think wouldn’t be much of an issue because the players are getting paid in rubles too and get hit as the same rate as everybody else. But it isn’t quite that simple. A good portion of the players from abroad are paid in euros or dollars, and supposedly immune to fluctuations in the ruble. But with the ruble where it is, the owners- who aren’t immune- have been forced to ask all players to accept renegotiated salaries based on a new exchange rate, which is going to result in across-the-board pay cuts of over 20%. And aside from that, soccer is a global marketplace. A player who doesn’t feel like he makes enough money in one country can very easily take his services to another country; another continent, where he feels he’ll get paid what he’s worth. The overseas players have already done this at least once: the time they left their respective homelands to play in Russia. There’s little to stop them from leaving again once their contracts expire.

Defending champion CSKA Moscow alone shows players from Brazil, Bulgaria, Cote d’Ivoire, Finland, Israel, Latvia, Serbia and Sweden, plus a Cameroonian in the U-21 squad. One doesn’t suppose any of them are too happy with recent developments.

The very real risk here is that the Russian league goes back to the way it was before the days of Vladimir Putin, when the clubs were net exporters rather than importers, and top domestic players couldn’t be held onto. As recently as 1996, Millwall- a midtable club in England’s then-First Division (the pre-Premier League top flight, for those recent converts to the game)- was able to snatch away Sergei Yuran and Vassili Kulkov from Spartak Moscow, which had finished third in the Russian league that year, the only lapse in what would ultimately become nine league titles in ten years. Ural Sverdlovsk Oblast, who currently employ players from Argentina, Austria, Chile, Iceland, Ukraine and Zambia, anticipates that they’ll be resorting to young domestics in the future- who play cheap- and odds are other clubs will be joining them.

Dialing down, however, may still be a better fate than what awaits the hockey league, the KHL. The KHL is regarded as the world’s second league after the NHL, and it isn’t cheap luring Canadian players away from the road to the Stanley Cup. Not all of the teams in the league are based in Russia, but the vast majority are, and some 40% of the players are from outside Russia. There is also no promotion/relegation mechanic; like in North America, there are conferences, divisions, playoffs, and ideally everybody shows up again next season. Ideally. In practice, there’s a fair amount of turnover. Last season’s runner-up, Czech club Lev Praha, proved too financially unstable to field a team this season. Spartak Moscow, which has a hockey branch, also had to withdraw for the same reason. KHL leadership, to this end, is looking at contracting the now-28-team league into something more manageable.

The Russian Premier League is 16 teams. Shrinking that league likely is not going to help matters. Shrinking the teams within it, though, appears inevitable.

World Cup Creep

Merry Christmas. I hope you all got what you wanted this year.

What you probably did not want is a World Cup in Russia. The ongoing brouhaha over Qatar aside, Russia has gotten its own share of corruption-based accusations regarding it having been awarded hosting rights to the 2018 World Cup. It hasn’t been quite as loud as Qatar- perhaps because people could see Russia actually pulling its weight in competition- but it’s certainly been there. One particular instance of recent note was that of FIFA official Harold Mayne-Nicholls of Chile stating that in his task of checking the technical merits of all 11 potential hosts for 2018 and 2022, England had “by far” the strongest bid, which made it highly suspect when they only got two votes in the 2018 tally and were eliminated on the first ballot. Aggression towards Ukraine, international sanctions and charges of racism have picked up much of the rest of the tab.

However, in a few months, several nations will no longer have to worry about it… because they will already have been eliminated.

Another thing you might not have wanted is Christmas creep, that phenomenon where the Christmas season seems to begin earlier and earlier every year, to the point of having Black Friday sales during Thanksgiving dinner and radio stations switching to Christmas music as early as October. The World Cup, though, follows the same pattern. I wrote about this on my old blog shortly after the final in Brazil, but I’ll reprise it here. Soccer never sleeps. Never. Mere hours after Germany lifted the trophy in Rio de Janeiro, MLS action was underway in Seattle as the Sounders defeated the Portland Timbers 2-0, in a match featuring several players who had been eliminated from the World Cup just a week earlier. The World Cup has slowly, over the years, crept further and further across the realm of the four-year cycle that governs it, not merely through the dramatic finale itself but through the qualifiers that feed it.

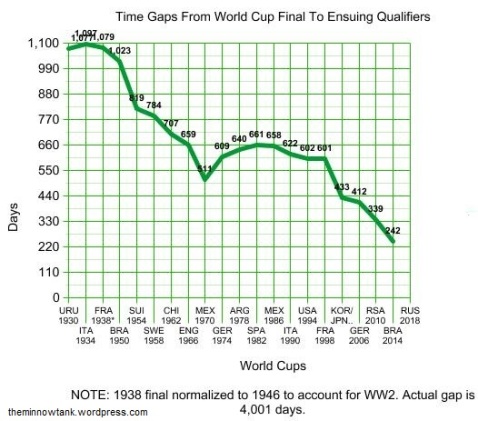

What I’m going to show you now is the time gaps between the date of each World Cup final and the date of the very first qualifying match for the next World Cup. And, of course, what that match was. In some cases, there have been multiple matches beginning on the same day; whenever possible, I took the match with the earliest timestamp. For the 1982 and 2002 qualifiers, those timestamps don’t exist, so I just used both.

Italy 1934: Final, June 15. Ensuing qualifiers began June 16, 1937, with Sweden/Finland in Stockholm, which Sweden won 4-0 (again, they would eventually qualify). Gap: 1,097 days.

France 1938: Final, June 19. Ensuing qualifiers began… okay, there was a little thing called World War 2 that got in the way, so the ensuing qualifiers began June 2, 1949, with Sweden/Ireland in Stockholm, which Sweden won 3-1 (once again, they qualified). Gap: 4,001 days.

Brazil 1950: Final, July 16. Ensuing qualifiers began May 9, 1953, with Yugoslavia/Greece in Belgrade, which Yugoslavia won 1-0 (and eventually qualified). Gap: 1,023 days.

Switzerland 1954: Final, July 4. Ensuing qualifiers began September 30, 1956, with Austria/Luxembourg in Vienna, wherein Austria cruised to a 7-0 spanking (and qualified). Gap: 819 days.

Sweden 1958: Final, June 29. Ensuing qualifiers began August 21, 1960, with Costa Rica/Guatemala in San Jose, which Costa Rica won 3-2. Gap:784 days.

Chile 1962: Final, June 17. Ensuing qualifiers began May 24, 1964, with Netherlands/Albania in Rotterdam, which the Netherlands won 2-0. Gap: 707 days.

England 1966: Final, July 30. Ensuing qualifiers began May 19, 1968, with Austria/Cyprus in Vienna, which Austria dominated 7-1. Gap: 659 days.

Mexico 1970: Final, June 21. Ensuing qualifiers began November 14, 1971, with Malta/Hungary in Valletta, where Hungary became the first away team to win an opener, doing so by the score of 2-0. Gap: 511 days.

West Germany 1974: Final, July 7. Ensuing qualifiers began March 7, 1976, with Sierra Leone/Niger in Freetown, which Sierra Leone won 5-1. Gap: 609 days.

Argentina 1978: Final, June 25. Ensuing qualifiers began March 26, 1980, with Cyprus/Ireland in Nicosia, which Ireland won 3-2; and Israel/Northern Ireland in Jerusalem, which ended in a scoreless draw (Northern Ireland would qualify). Gap: 640 days.

Spain 1982: Final, July 11. Ensuing qualifiers began May 2, 1984, with Cyprus/Austria in Nicosia, which Austria won 2-1. Gap: 661 days.

Mexico 1986: Final, June 29. Ensuing qualifiers began April 17, 1988, with Guyana/Trinidad and Tobago in Georgetown, which Trinidad and Tobago won 4-0. Gap: 658 days.

Italy 1990: Final, July 8. Ensuing qualifiers began March 21, 1992, with Dominican Republic/Puerto Rico in Santo Domingo, which Puerto Rico won 2-1. Gap: 622 days.

United States 1994: Final, July 17. Ensuing qualifiers began March 10, 1996, with Dominica/Antigua and Barbuda in Roseau, which ended in a 3-3 draw. Gap: 602 days.

France 1998: Final, July 12. Ensuing qualifiers began March 4, 2000, with Trinidad and Tobago/Netherlands Antilles in Port of Spain, which Trinidad and Tobago won 4-0; and Honduras/Nicaragua in San Pedro Sula, which Honduras won 3-0. Gap: 601 days.

Korea/Japan 2002: Final, June 30. Ensuing qualifiers began September 6, 2003, with Argentina/Chile in Buenos Aires, which ended in a 2-2 draw (Argentina would qualify, the most recent team in an opener to eventually do so). Gap: 433 days.

Germany 2006: Final, July 9. Ensuing qualifiers began August 25, 2007, with Tahiti/New Caledonia in Apia, Samoa, won 1-0 by New Caledonia. Gap: 412 days.

South Africa 2010: Final, July 11. Ensuing qualifiers began June 15, 2011, with Montserrat/Belize in Couva, Trinidad and Tobago, won 5-2 by Belize. Gap: 339 days.

Brazil 2014 wrapped on July 13. While Africa, South America and Europe have yet to set dates, we do have dates for the other three continental qualifiers. The earliest of those three is that of Asia, who announced about a week ago that they will commence on March 12 with teams yet to be drawn, making for a gap of 242 days, and the first round, a set of two-legged ties between the weakest sisters of the continent, will conclude on March 17, as part of an aggressive strategy to respond to the continent’s subpar performance in Brazil. On the 23rd, before the first corpses of the Cup are even cold, North America will also set off on the road to Moscow.

The Loneliest Al-Shabab Supporter

On Friday, December 12 in the top-flight Saudi Professional League, Riyadh’s Al-Shabab picked up a 1-0 away win over Jeddah’s Al-Ittihad. Midfielder Abdulmagid Al-Sulaihem scored the game’s only goal in the fifth minute of 2nd-half stoppage time. One round of matches later and just about halfway through the season, Al-Shabab, as of this writing, sits third in the 14-team league table, which if the season ended today would earn them entry into the AFC Champions League. Al-Ittihad sits three points behind Al-Shabab in fifth.

This is not the important bit about the match. It’s just my personal policy to never let the result of a key match in a given story go unmentioned. I hate when people mention a game where something happened and then don’t say who won the darned thing. So there it is, right upfront.

The important part of the match happened in the stands. What happened was that a woman bought a ticket online and attended the game. She was then ejected for being a woman who attended a soccer game.

There’s a video of the affair, but really, the photo viewable here will suffice. What you see is a woman in the Al-Shabab supporters section a pretty heavily male disguise- a hat, sunglasses, long-sleeved shirt, pants, all in the black and white colors of Al-Shabab. This qualifies as a male disguise because women in Saudi Arabia are required to wear an abaya- the loose-fitting black dress- in public, and most wear a niqab as well (the face-covering veil). Obviously, it didn’t work; someone in the stands got suspicious and ratted her out. And, given when the only goal of the game happened, that means she missed seeing her team win in the dying moments of the match.

In fact, there are a lot of restrictions on women in Saudi Arabia. There’s a debate going as to whether to allow women to drive a car (during daylight hours, with the consent of a male relative, after their 30th birthday, with a man in the car when outside of the city, while conservatively dressed, and for the love of all that’s holy no makeup). Women can’t leave the house without a male chaperone; they can’t try on clothes at the store in a changing room (they end up having to use the toilet); there’s no physical education for girls in public schools. In the Asian Games in Incheon, South Korea back in October, Saudi Arabia was the only one of the 45 competing nations not to put women on their team. Women are making a concerted push for civil rights, in some cases exploiting the custom of separating the genders in public to create women-only schools and businesses, and however slowly, that is the direction things are going. But there is a hellaciously long way to go, and change comes at a glacially slow pace.

Which is how you get to circumstances such as what happened in Jeddah. Separation of the genders in public means a soccer match between male teams has been a male-only space until 2013, when women were first permitted to attend sporting events, with stadiums newly built to receive women-only sections. Back in 2012, there was rumored to be a method in the works at the very stadium where this happened, the opened-in-May King Abdullah Sports City, and at least as far as VICE is concerned when they reported on the stadium’s opening ceremony, they followed through. But even VICE was still talking in the future tense, referring to it as something still yet to happen, and I haven’t seen their confirmation corroborated anywhere else or anyone make note of the balconies actually being in place. The fact that the fan noted that she was able to buy a ticket tells me that the issue here still lies in her mere attendance and not in the location of her seat.

The woman has since been released after making bail and signing a statement apologizing and promising not to do it again. She also reasserted that she is, in fact, a fan of Al-Shabab.

Let’s repeat that. A woman was arrested, spent about a week and a half in jail, paid bail, was made to apologize and promise not to repeat her actions of… attending a soccer game. As a matter of perspective, I write this from a country where the current largest issue regarding women and soccer is that the national team dropped out of the #1 ranking for the first time since 2008.

Saudi Arabia does not have a women’s national team at all.

The Ballad Of The Bull

When it comes to extreme sports, Red Bull hopes you’ll think of them. The energy-drink business demands as much: pound this energy drink and look at all the hardcore stuff you’re just gonna be jacked to the gills to get out there and do. Red Bull is near-ubiquitous at the ragged fringes of the sports world, often devising their own events just so the Red Bull label can be slapped on them. There’s the freestyle motocross competition Red Bull X-Fighters. There’s the skatecross event Red Bull Crashed Ice. There’s the stunt-pilot racing series Red Bull Air Race. There’s the adventure race Red Bull X-Alps. In 2012, they took a downhill run in British Columbia, built ramps and obstacles all over the mountainside in the summer, waited for an entire winter’s worth of snow to dump on it, and then sent people down it as-is, calling it Red Bull Supernatural. When Felix Baumgartner went skydiving from 24 miles up in 2012, the official title of the jump was, sure enough, Red Bull Stratos. And that is only a fraction of Red Bull’s sporting presence, in addition to the two Formula One teams they run.

Excursions into the soccer world, though, have proven far more problematic.

The story of Red Bull’s soccer saga begins in Salzburg, Austria. SV Austria Salzburg came along in 1933 as the result of a merger of two other clubs. A folding and immediate refounding in 1950 aside, Salzburg’s basic story is not all that dissimilar from that of some other high-level clubs: a maiden voyage in Austria’s top flight in 1953, an inaugural European showing in the 1971-72 UEFA Cup (a first round loss to Romania’s UT Arad), an inaugural Champions League showing in 1994-95 (under the ultimately temporary renaming Casino Salzburg), where they came in third in their group behind Ajax and AC Milan and were sent out of the running. Going into the 2005-06 campaign, Salzburg had three league titles to their name, all from the mid-90’s. They were still settling into their new stadium, opened in 2003. The one fly in the ointment was that they’d been slipping down the table. In a ten-team top flight, they’d ended the previous season in ninth place. There was only one relegation spot, which had gone to Schwarz-Weiß Bregenz, 15 points below Salzburg, after Bregenz had incurred so many financial problems that they were forcibly relegated to the fifth tier. Salzburg couldn’t count on that kind of personal good fortune again.

This is where Red Bull entered the picture. Wishing to enter the soccer market- the world’s biggest sport! It’s only natural!- Red Bull, which is based in Fuschl am See, Austria, 12 miles east of Salzburg, decided it would be a good idea to buy the local team, which just so happened to be Austria Salzburg, and rename it Red Bull Salzburg. This was not Red Bull’s mistake. Austrian clubs have seen their share of corporate rebrandings. Austria Salzburg itself had seen a corporate rebranding under which they’d won all three of their titles. That wasn’t anything new. Had that been the end of it, the fans would have been fine with it. They were in relegation territory. Yes, sure, bring in that sweet sweet Red Bull money and come bail us out.

Red Bull’s mistake was to announce that Red Bull Salzburg was “a new club with no history”. Austria Salzburg was dead. The club color, purple, was to become Red Bull’s red and white. The past seasons would not be recognized. The foundation date was to be altered from 1933 to 2005, a move only stopped when Austria’s national federation told Red Bull in no uncertain terms that the 1933 date was to remain as a condition of being granted a license to compete.

In the regions of sport in which Red Bull usually deals, sponsors are a critical part of the process. Without the sponsors, many of the competitions simply do not have the money to go forward and are relegated to ad-hoc backyard hobbying. Athletes in those competitions- auto racing, the X-Games set, one-off stunts like Baumgartner’s- have no problem being emblazoned with sponsor logos if it will get them out on the field, and typically actively seek them out.

In sports with city-based teams, such as soccer, things are different. When teams are geographically dispersed, when they each have a designated home, the community in which they are based will think of the team as part of that community. The team will usually have a name that is at least partially geographically-based, and the club culture is in some way bound to reflect the local culture. Violet was a color brought over by one of the pre-merge clubs in 1933, Hertha Salzburg. The team history includes players that died fighting in World War 2. Added to the on-pitch achievements- a UEFA Cup final that was theirs and theirs alone; three league titles that were theirs and theirs alone- these were not things that fans could just wipe away.

But Red Bull was adamant about it. All attempts to reassert at least some of Austria Salzburg’s old culture were forcefully suppressed. Signs torn down. Fans denied entry to the stadium. Being told that their grievances were “kindergarten stuff”. Eventually, the supporter groups threw up their hands.

Then they took a new team, dubbed that Austria Salzburg, bestowed the entire club history upon it, recruited the best possible players they could rally to the cause, and started storming from the seventh tier up. Four straight promotions later, they found Red Bull Salzburg’s youth team waiting on the third tier. They have yet to proceed any further, but came close last season before faltering in a promotion/relegation playoff.

Meanwhile, Red Bull Salzburg’s youth team was relegated to the fourth tier. And when they soon took the senior team into European competition, as was almost inevitable, they promptly found out that because Red Bull is not an approved sponsor of the UEFA Champions League or Europa League, they cannot name themselves Red Bull Salzburg. During their stay, they must name themselves SV Salzburg. And every other team in the competition, they find, would love nothing more than to run them over for symbolic purposes. After all, they don’t want that to happen to their club.

But this was not the end of Red Bull’s soccer aspirations. They could get this right; they were sure of it. What about MLS? The United States is pretty used to sponsors everywhere, right? It’s a growing league. And if they’re going to buy an American team, it would make sense to buy in New York, the largest market of all. In 2006, Red Bull thus purchased the NY/NJ MetroStars, rebranding them the New York Red Bulls. However, learning from the Salzburg affair, they didn’t attempt to wipe away the MetroStars history. And they’d actually be increasing the geographic footprint of the name, as in 1998, the ‘NY/NJ’ part was dropped, leaving only ‘MetroStars’. It seemed pretty low-risk.

Unfortunately for Red Bull, wiping the history away would probably have been doing the MetroStars a favor. Intended to be one of MLS’ marquee clubs, the MetroStars were instead their most disappointing. By the time Red Bull came along, they were the only remaining inaugural club not to have won a league title or the Supporters’ Shield, awarded to the regular-season champion. They also had a curse, the Curse of Caricola, named for Nicola Caricola, who scored an own goal to lose the MetroStars’ inaugural home game 1-0 against the New England Revolution.

And while the United States can bear some amount of sponsorship, it’s in different places than most other countries. American sports fans are more accepting of corporate stadium naming, but less accepting of sponsors on a team jersey. And corporately naming a team is unheard of. Austria Salzburg had precedent from which to accept the name Red Bull Salzburg, even if they ultimately rejected it. American fans had no precedent readily apparent, so some degree of mockery was always going to happen.

Plus, unlike in Austria, where Red Bull could spend whatever it needed to spend to secure victory, MLS has a salary cap. Their corporate might meant nothing, beyond the ability to pay for cap-exempt Designated Players. The Curse of Caricola continued into 2013, when the Red Bulls finally secured a Supporters’ Shield, The attendance has been stagnant, and with New York City FC on the horizon, the Red Bulls, who play in New Jersey, face the very real possibility of becoming the second team in their own metro area.

Attempt #3 brought Red Bull to Brazil. Okay. We’ve learned that rebranding a club just leads to misery. How about if we just found a new club? In Brazil! Soccer’s a religion down there! We can make a new club, rise through the ranks, we won’t be stepping on any fans’ toes and any we do get are bound to be cool with us. This can’t go wrong, right? And thus in 2007, Red Bull Brasil descended upon Campinas, probably hoping for a fast ascension. The way the Brazilian pyramid works is that there are four national levels, Series A through D, and under that are state-level tiers. A through C work pretty much like you’d expect, but Serie D, functioning like a cup competition, completely resets every season, stocked with the bottom teams from Serie C along with the top teams from each of the state-level tiers. If you fail to promote out of Serie D, you have to win in your state again to get another chance. That established, Red Bull Brasil was entered into Sao Paulo state’s fourth tier, meaning eighth tier overall. For a stadium, they groundshare with more-established Ponte Preta.

Let’s leave the eighth tier aside for the moment. There are explicitly corporate teams in the world, called ‘works teams’, where the club was founded by a local company or the employees of same, so they have something to do when they’re not working. Sometimes those clubs even work out and end up getting players who aren’t actually employees but are good at playing soccer. Some of those clubs are even Brazilian. A club founded by a fabric factory became Bangu. Corinthians was founded by railway workers. It can work.

If the company is locally based. And Red Bull, as we’ve established, is based in Austria. So they don’t have the built-in employee base that works teams would normally have. They just have people who’ve seen cool videos on YouTube who aren’t already pledged for life to someone far larger. In essence, Red Bull Brasil is left with a developmental team until such time as they figure everything out. In addition to the U-15 and U-17 teams they decided to also form. Paying abnormally high salaries doesn’t help much in the eighth tier. Down that low, salaries aren’t even much of a concept. If you’re good enough to be paid to play soccer, you’re generally too good for the Brazilian eighth tier. They’ve made it up to the sixth, but it’ll be a long time before you see them make much of themselves.

In 2008, another low-tier club was founded, but this time in Africa. Red Bull Ghana was created in the city of Sogakope, and currently plies their trade in one of Ghana’s lower tiers. Ghana’s national federation website doesn’t list below the second and Red Bull isn’t there; likely, they’re in the third. Ghana IS a place where a corporation can just drop in and start a club. The problem, though, is that the logistics of doing so are not generally cost-effective. Given the challenges of soccer in Africa, this would never become a club that grabs the world’s attention. Even if it became the best club in Africa, getting due recognition as an African club would present its own set of challenges. But as an academy product- an academy product with Red Bull’s money behind it- it’s certainly something that a kid looking to be the family breadwinner could sign up for without much fear of getting scammed. Plus it’ll help sell a lot of Red Bull in Ghana.

In the meantime, Red Bull, refusing to give in, entered the German market. The tactic this time was to take their act into the city of Leipzig. In 2009, Leipzig stood as the 12th-largest city in Germany, but they sit in the former East Germany, which faltered as a whole after the reunification and typically can only enter one or two clubs into the Bundesliga, at most. (This season, they don’t have any.) Despite being the only East German city called to host games in the 2006 World Cup, their clubs were very weak and very far down the board compared to Germany’s other major markets. The idea here was, find a club in Leipzig, buy them, and drive them up the pyramid, on the theory that the locals would be happy just to have anyone come in that would get them a halfway-decent team.

The question, though, was what team. Back in 2006, right on the heels of buying Austria Salzburg, Red Bull had made an attempt to purchase Sachsen Leipzig, but after months of protests and even violence, Red Bull abandoned the attempt. Three years later, they set their sights on SSV Markranstadt. Or at least, they set their sights on Markranstadt’s license, which they duly received. Markranstadt could keep going in the amateur ranks (and go get a new license if they wanted), while Red Bull dealt with the mounds of red tape and local rival vitriol now before them, red tape that was only navigable because they’d bought in the fifth tier and not any higher up, where the requirements are more stringent.

For example, German clubs are required by law to be set up as member-run organizations. Members must own 50+1% of the club; a company cannot own any more than the remainder. Red Bull responded to that by buying 50-1% and making sure that of the 11 club members (Bayern Munich, for comparison, has some 224,000 members), all have a connection to Red Bull. As a condition of getting the license, the club also could not be called Red Bull Leipzig. Solution: call it “RasenBallsport Leipzig”, for ‘Leipzig lawn ball sports”, and then just ask people to colloquially call it “RB Leipzig”, because acronyms are fun. In general, if there was a rule designed to enforce that clubs be governed by the fans, Red Bull skirted it in the biggest legally-possible way. And then they went to work climbing up the ranks.

Sachsen Leipzig and fellow local rival Lok Leipzig naturally went to work protesting corporate influence in German soccer. At one point, Sachsen supporters wrote a protest message into Red Bull’s pitch with herbicide. When RB Leipzig soon blew past them and got into higher tiers, though, the Leipzig rival anger died down, in recognition that, after all, there was a decent Leipzig team now. But it was replaced with anger from larger fanbases, fearful of what Red Bull represented and might herald for their own clubs. This season, Red Bull is nearing their goal: they’re in the second tier and in the mix to potentially enter the Bundesliga, and they’re seeing no shortage of venom from the nation at large. FC St. Pauli called for Red Bull to be denied promotion to the second tier based on their only obeying the letter of the law and not the spirit, a call that was ultimately denied. The second-tier license was, however, made dependent on loosening up on the membership standards (they now have a whopping 300). In a game against Union Berlin, Union supporters work black ponchos and engaged in 15 minutes of stone silence. (Then Union won 2-1.) Fans nationwide, if nothing else, are angry that their clubs have fought and scrapped and bled all these years to get where they are, and then Red Bull just rolls in with all their money and buys whatever they want.

If Leipzig, Salzburg, New York, Campinas or Sogakope finds that someone from one of the other four clubs would help them out, for instance, the barriers to getting that player aren’t going to be very high. As long as Red Bull is paying, it really doesn’t matter what club’s balance sheet it goes on.

And this is the crux of the entire saga. No new teams have been purchased since Leipzig. But maybe they don’t need to be. New York is one matter. In MLS, in addition to the salary cap, the rules for acquiring a player from outside the league are quite complicated and serve specifically to prevent any one club from being able to sign so much overseas talent that they overwhelm the others. There’s no real desire to have another New York Cosmos situation, where people only consider one club to be worth watching. So aside from a smattering of superstars, the odd Thierry Henry or Tim Cahill, the Red Bulls aren’t able to load up the roster and, thus, run away with the league. Outside the United States, though, including in Europe, it is a Wild West financial model for the most part. If you can sign a guy and pay for him, you go right ahead. The very first thing Red Bull did in soccer was run away with the Austrian league, and they hope to run away with the German league as well. If there’s budding talent in Brazil or Africa, maybe Red Bull can get to them before anyone else does and feed them to Salzburg and Leipzig. And this doesn’t even count the youth programs run by all of the clubs.

Red Bull has hit a point where they are never going to make themselves a popular presence in the soccer world. The bad blood has run too deep, too fast. So instead of popularity, they have simply opted for power. Do what it takes to win, by whatever means, and at least get Red Bull’s name forced onto the biggest possible stage and associated with winning, and thus, increase sales of Red Bull. And thus, to the consternation and fear of opposing fans, Red Bull has brought their extreme-sports sensibilities to bear upon them.

For when you face a Red Bull club, you really face five.

Club Kiwi

The Club World Cup is underway in Morocco. Most soccer fans tend to pay the Club World Cup little attention. As a competition that brings together all six continental champions, it technically decides the world champion of the club game. However, many fans- the European fans especially- view this as unnecessary and silly, because they consider the European champions to be, by permanent default, the automatic world champions. After all, the top talent always funnels into Europe, doesn’t it? It makes sense. Why bother even holding it, really?

Personally, I don’t think it’s that simple. First off, in the Club World Cup era- the era from 2000 on- there have been ten competitions. Europe has only won six of them. A majority, yes, but hardly domination given that the other four were won by South America, a continent that heavily supplies Europe with top talent and sometimes even manages to hang onto it. In the previous incarnation of the competition, the Intercontinental Cup– which only involved Europe and South America-, South America actually beat Europe 22-21. (Of course, one factor in this may have been the European champion flat-out refusing to play, leading to the European Cup runner-up taking the helm instead. When that happened, South America won 5 cups to Europe’s 1.) Europe may have the most famous, most expensive teams, and maybe they are the best.

But the thing about being the best in your sport is you don’t just get to rest on that laurel. There is always someone out there that thinks they can yank the title off of you, and you have to go on continually, constantly defending it. You never know when someone will. Especially in a sport with global reach such as soccer. There is an entire planet’s worth of talent out there, and it all wants to be the best. For all that Sepp Blatter has done wrong over the years, I believe that expanding things to involve all six continents was one thing he’s done right. For all the complaining Europe does about how having to play the other continents is irritating at best, for all the attempted minimizing they do of any game they lose to those other continents about how they weren’t going all-out because of how silly the whole affair is, this isn’t really about what Europe wants. It’s about giving everybody else a fair shot at Europe. It’s about getting Europe, or at least their representative, to go out and defend the realm. It’s about giving clubs on the other five continents a concrete carrot on a stick: win your continental title and you could get a free shot at Real Madrid or Bayern Munich or whoever it is Europe sent this year.

And if they convert on that free shot and manage to become the last team standing? Well, guess who’s world champion.

There’s a club in Tanzania, haven’t heard much from them in a while but they picked up some human-interest-story press a few years back, called Albino United. Last I saw, they were in the third tier. The club, playing in unkempt clearings wearing ill-fitting clothes, exists chiefly as a method of proving the team’s mere humanity. Albinos are not considered as such by many in Tanzania. Instead, they are viewed as spare parts, commodities to be killed, chopped into pieces, and their individual body parts made into lucky charms and talismans by witch doctors and sold to all manner of the citizenry. By forming a club, the players, even though they must play at night so that their skin isn’t burned by the midday sun, prove that they are just as human as the other team on the pitch. Or at least, that’s the hope.

In only five years, even a club as small and with goals as humble as theirs can, theoretically, become world champions, because the structure of soccer permits it. The first three years would get spent working their way up the Tanzanian pyramid, the fourth, should they win a league title, would be spent fighting through the CAF Champions League, and if they won that, the fifth year would feature a date with the other continental champions in the Club World Cup. And if they somehow won that too, this little club of players just trying to prove that they’re human would become world champions, the only team left to drip through an incomprehensibly massive global funnel.

Is it likely? Oh Jesus no. I wouldn’t bet a penny on it because I don’t want to lose my penny. But however unlikely their odds, even if it’s one in a billion, those odds are not zero. The system allows for it in a way that other team sports do not, in part because soccer doesn’t have any one league that is taken for granted as the world’s perpetual best. The NHL is known as the best hockey league, the NBA is known as the best basketball league, MLB is known as the best baseball league. In soccer, it’s an open question, and because it’s an open question, all the national leagues battle each other for positioning. Maybe La Liga is the best one year, but maybe the Bundesliga or English Premier League or Serie A will be the best next year, and all manner of leagues below fight for every scrap of recognition they can get. The J-League, A-League, Liga MX and MLS fight to rise through the ranks, while Campeonato Brasileiro Série A, Ligue 1 and the Eredivisie struggle to keep from falling behind. They all want their shot, and through the Club World Cup, they all get it. And Europe aside, they all relish the opportunity.

Converting that shot, though, is another matter. Which brings us to the club to which the Club World Cup means more than probably any other on the planet, New Zealand’s Auckland City. They’ve been to more Club World Cups than anyone else, attending for the sixth time this year as champions of Oceania, and the fourth consecutive time. But as the representatives of the weakest confederation, the OFC, and as an amateur team, they’re prone to taking the most ridicule, and their status led in 2007 to the tournament taking its current form: the Oceania champions play the league champion of the host nation in the first round, then Africa, Asia and North America enter in the next round, with Europe and South America handed byes to the semifinals. Because Oceania- because Auckland City- is so far behind in status compared to the champions of the other continents, they have to play an extra game, against the host nation (or the next team down in the continent, if the host has already qualified), just so that the locals will stay interested.

When Auckland City- or their local rivals Waitakere United, with two appearances of their own- have shown up, results have pretty much borne that out.

*In 2006, Auckland lost 2-0 to Egypt’s Al-Ahly, then lost 3-0 to South Korea’s Jeonbuk Hyundai Motors.

*In 2007, Waitakere lost 3-1 to Iran’s Sepahan.

*In 2008, Waitakere lost 1-0 to Australia’s Adelaide United.

*In 2009, Auckland recorded their first win, 1-0 against host UAE’s Al-Ahli, but then lost 3-0 to Mexico’s Atlante and 2-0 to DR Congo’s TP Mazembe.

*In 2011, Auckland lost 2-0 to host Japan’s Kawisha Reysol.

*In 2012, Auckland lost 1-0 to host Japan’s Sanfrecce Hiroshima.

*In 2013, Auckland lost 2-1 to host Morocco’s Raja Casablanca.

But then there’s this year. In the opening round, Auckland City survived a 4-3 penalty shootout to defeat host Morocco’s Moghreb Tetouan, which all by itself was enough to cause the resignation of Moghreb’s manager. In Round 2, Auckland then upended Africa’s actual champions, Algeria’s ES Setif, 1-0, setting up a date with Argentina’s San Lorenzo on Wednesday. (The other semifinal features Real Madrid and Mexico’s Cruz Azul, who defeated Australia’s Western Sydney Wanderers 3-1 in the other Round 2 match.)

By getting this far, Auckland City will be dealing with something that any of the other clubs in the competition might deem more or less inconsequential: the prize money. The winning club will receive $5 million US. For Real Madrid, a club whose weekly payroll, at least as of last month, comes out somewhere in the $2.6 million range, this is a laughable prize. For Auckland, even the lesser prizes are crucial. Even though they’re an amateur club, or maybe because they are, the expense of competing overseas can eat into finances quickly, as the club has to secure the ability of their players to be away from their day jobs for the length of the tournament, not to mention the costs of travel. The agreement in New Zealand is that half of the money any of their clubs earns in the Club World Cup goes straight to the national federation and split evenly between all the clubs in the top flight. After that, the combined costs of competing in the OFC Champions League that serves as qualifying for the Club World Cup, and setting up camp in Morocco, comes out to somewhere in the $200,000 range. That doesn’t include flying out for the pre-tournament festivities- including the draw which to Auckland is almost superficial because they already know who they’re playing in the first round, which most of the time is their only round- or any unexpected costs of travel, such as added costs for baggage. In addition, should they manage to advance, that means their players will be away from their jobs longer, meaning Auckland sometimes has to pay off their employers so the players don’t get fired.

If Auckland were to lose their first game, they’d have collected $500,000. They would have more or less broke even. Last year, when the airline charged them extra for baggage, they actually lost money, a near-crippling amount in fact. Having gotten to their current point in the tournament, they’ve assured themselves of at least $2 million. If they somehow manage to beat San Lorenzo too, that prize will double.

Auckland’s goals run deeper than purely the money, though. There’s a reason that the best club Oceania has to offer is an amateur team. Oceania’s sport is not soccer. It’s rugby. New Zealand’s rugby team is world-renowned. Cricket comes second, where New Zealand is also competitive, even if they don’t win very many trophies. Third would probably be netball, which since this is an American-based site, and since netball isn’t a thing in America, I should describe as ‘basketball without the backboard and without men’ (the sport’s governing body doesn’t even recognize men’s netball). Again, the national netball team is among the best on the planet, frequently challenging for honors. In soccer, New Zealand does not challenge for honors. Beating up on the likes of Fiji, Papua New Guinea and New Caledonia is not sufficient, as their Oceanian bretheren are even less developed and sometimes barely have soccer programs at all. New Zealand is only even the best in Oceania because they inherited the title when Australia bolted for Asia in 2006 just to get decent competition. Kiwi sports fans want to see some winning, against quality opposition, and the national soccer team, the All Whites, is winless in its last nine matches.

This will not change over the course of a single one-off tournament. But defeating another continental champion, really any other continent, is enough to raise an eyebrow or two back home. And now it’s given them their shot at the big boys. San Lorenzo beckons, and while the odds are still long, should Auckland City win that too, chances are they’ll have Real Madrid right behind them, which is almost guaranteed to get New Zealand’s undivided attention, even if only for a day.

For Real Madrid, it would be little more than just another game, another motion to go through, another $5 million, another trophy for the pile, and another delusional opponent thinking it can stand against European might. For Auckland City, the moment would be priceless.

The Champions Of Romania

If you’ve heard of one Romanian club, odds are it’s Steaua Bucuresti. They’re the ones larger clubs out west are most likely to run into in the UEFA Champions League, even though this year they’re in the Europa League after qualifying defeat at the hands of Bulgaria’s Ludogorets Razgrad, who themselves just finished last in Champions League Group B. Two-time defending league champions, Steaua has a Romanian-best 25 league titles total, with #26 well on the way, to go along with an also-Romanian-best 21 national cups and the 1986 European Cup.

Steuea is also the place where the world in general learned the name Gheorghe Hagi, who showed up on what was to be a one-match loan for the 1987 European Super Cup and left for Real Madrid in the aftermath of the 1990 World Cup.

In the Europa League, Steaua is up against it. With one game to go, they sit third in their group, two points behind Denmark’s Aalborg BK, and to advance to the knockouts, they’ll need to not only beat visiting Dynamo Kiev on Thursday, they’ll also need Aalborg to lose or draw when they visit Portugal’s Rio Ave. But that has become a secondary problem for Steaua.

Steaua Bucuresti’s identity, aside from that which they create between the white lines, is tied to their association with the Romanian army. Army officers were the ones to found the club back in 1947, one of the nicknames they’ve acquired over the years is ‘Militarii’, their colors are that of the Romanian flag, and even though the club privatized in 1998, they’re still seen as the army club. Their stadium remains the property of the Ministry of Defense.

And so does the intellectual identity. When the club was privatized, it was set up to be run by a nonprofit, AFC Steaua Bucuresti, and run by Viorel Paunescu. Paunescu had permission to go ahead and keep using the Steaua identity, which was great, except for the fact that there were also shares in this organization that could be bought and sold. Paunescu was a cripplingly incompetent owner, and drove the team deeply into debt, which was at least partially combated by having some of the shares go to the creditors. This is when politician/buisinessman Gigi Becali, who doesn’t appear to have been one of the creditors, rode into the picture, managing to buy up 51% control of the club through methods that to this day haven’t fully been explained. In 2003, Becali, now in control, took the club public. But in taking control, he also took on the club debt, which he proceeded not to pay. In 2006, the Revenue Service targeted him and tried to freeze his assets to get the money, but lost in court when they tried to force payment. This is when Becali unloaded the shares onto easily-controllable friends and family.

A long string of other corruption-related run-ins with the law involving bribery, forgery, unlawfully detaining people and abuse of power resulted in Becali being sent to prison last year. But that still doesn’t get us where we’re going on our particular matter today. Clearly uncomfortable with a man like Becali representing their brand, the Ministry of Defense sought to revoke Steaua’s right to use the club imagery. This past Thursday, December 4th, Romania’s highest court ruled in the military’s favor, stripping Steaua Bucuresti to the rights to the name, logo or team colors, effective immediately. That meant that on Sunday, when the club faced currently relegation-zoned CSMS Iasi (an effect of the Romanian top flight downshifting this year from 18 teams to 14, making for six relegation spots instead of the usual two), Steaua was not able to call itself Steaua. On the scoreboard, only an empty square was present to stand in place of the logo. The club’s name was replaced with ‘GADZE’ on the scoreboard- ‘hosts’. The PA announcer referred to them as “the champions of Romania”. The club came out in a plain yellow jersey, their normal away outfits; their regular home colors are red and blue. Everywhere the team’s name could be removed, it was, and when it couldn’t, it was covered up. (Steaua won 1-0.)

The Ministry of Defense isn’t completely hardline. Tomorrow, for the Europa League game against Dynamo Kiev, ‘the champions of Romania’ will be permitted to once again call themselves Steaua Bucuresti. They have a one-week reprieve for the purpose, which is why their website hasn’t been stripped. But that’s pretty much it. Any future use is to be done at the pleasure of the Ministry of Defense, and given that things have reached this point, Steaua shouldn’t count on much more charity beyond that. They may end up resulting in a name change, though the more likely case is they’ll have to start paying for naming rights.

Of course, the money for something like that will have to be found. Beating Dynamo and having Aalborg lose to Rio Ave would certainly help towards that.

Colombia And The Clinton List

In 2011, at the blog of mine that preceded the Minnow Tank, I talked about an executive order from Bill Clinton that, it would eventually happen, had a direct effect on the Colombian soccer scene. As per this site’s mandate, and events that transpired a few weeks ago (before launch), I feel it proper to revisit that order here.

The order was Executive Order 12978, signed on October 21, 1995. The order freezes the American assets of any person or organization connected to particular Colombian drug kingpins, and bars anyone who does business in or with the United States from also doing business with those frozen entities. In Colombia, being so frozen is known as being on the Clinton List. While focusing specifically on Colombia, the order was strengthened in 1999 when Congress passed the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act, colloquially called the Kingpin Act. The Kingpin Act essentially extends the Clinton List to be able to be applied to any country, not just Colombia.

The thing is, of course, that Colombian drug kingpins like soccer as much as the rest of Colombia. And not only do the kingpins have, shall we say, significantly more power to influence events than the average Colombian citizen, but investing in soccer clubs is seen as a viable method through which to launder money. And if you’re going to funnel money through a soccer club, it might as well be your favorite club. The country’s biggest kingpin, Pablo Escobar, was a big fan of Atletico Nacional, and spent a fair portion of his drug money to finance the club. Atletico National was also the primary club of Andres Escobar (no relation), the defenseman who was infamously shot to death in Medellin five days after giving up the own-goal that would knock Colombia out of the 1994 World Cup. ESPN’s 30 For 30 episode ‘The Two Escobars’, which you can watch here if you haven’t already, contends that nobody would have dared to touch Andres had Pablo not died the previous December.

Since Pablo had died before the creation of the Clinton List (though he assuredly was an inspiration for it), Atletico Nacional managed to dodge being affected by it. America de Cali, though, was not so lucky, as they had drug patrons of their own in the form of Gilberto and Miguel Rodriguez Orejuela. The Orejuelas were two of the four original kingpins placed on the list, America de Cali were added in 1999 after the Orejuelas were tossed in jail (Gilberto is today an inmate in Canaan, Pennsylvania; Miguel is held in Edgefield, South Carolina). It meant that not only would any US-related sponsors not want anything to do with the Red Devils, they also couldn’t financially benefit from international competition… which meant they missed out on a $200,000 payday when they won the 1999 Copa Merconorte. They were reduced to paying their players about $3,000 a month. (MLS’s minimum wage for 2014 was $36,500, by comparison.) It took until 2013 for the club to finally extricate themselves from the Clinton List.

By then, another club had been sweating bullets over the potential of being added themselves. Independiente Santa Fe was staring down the list in 2010 after the arrest of four traffickers who sought to launder their money by buying part of their club. Ultimately, though, Santa Fe skated, and remained off the list.

But Pablo Escobar’s role in the story persists. The fate that his death spared Atletico Nacional was simply transferred to another club, Envigado FC.

It seems bitterly ironic now that as recently as September, VICE’s Joseph Swide told of Envigado’s having served as a beacon of Colombia’s future. What Swide had in mind was that El Equipo Naranja was a youth pipeline, with three of their alumni being selected for the Colombian squad at this year’s World Cup, all midfielders: Freddy Guarin (currently of Inter Milan), Juan Fernando Quintero (currently of FC Porto), and golden boy James Rodriguez (of AS Monaco as of the Cup; he signed for Real Madrid less than two weeks after it ended). But he also told of what happened when Pablo Escobar was hunted and brought down for good.

Envigado FC was founded in 1989, and as of now lingers around the lower-mid reaches of the Colombian top flight, not competing for honors, but not really a relegation threat either. It’s named after its hometown. But one might be mistaken for thinking that it’s actually named for La Oficina de Envigado- the Office of Envigado- which began life as the enforcement wing of Escobar’s Medellin Cartel. The founder of the club was Gustavo Adolfo Upegui Lopez, a personal friend of Escobar, who himself grew up in Envigado. A few years later, the Office split from the Medellin Cartel due to a falling-out between Escobar and Office head Diego Murillo Bejerano; the Office would go on to aid in the manhunt that led to Escobar’s death. The Office assumed the contacts that made Escobar so powerful, and as a result, they became the new top dog in the Colombian underworld. Gustavo Adfolfo was killed in 2006 by the Office; Envigado FC passed to his son, Juan Pablo Upegui Gallego.

The Office was added to the Clinton List on June 26. On November 19, both the club, and Juan Pablo personally, joined them there. As the official press release from the US Treasury Department states, “Upegui Gallego is a key associate within La Oficina and has used his position as the team’s owner to put its finances at the service of La Oficina for many years… The diversity of those designated today – targeting a variety of companies and influential cartel members, including the majority owners of a professional soccer team – will strike at the financial core of this violent criminal network and impede its efforts to operate in the legitimate financial system.” Several of Envigado’s shareholders also landed on the list. If Envigado FC wants off the list, each and every ounce of connection to the Office, including every single person now on the list that is involved with the club, must be completely financially and personally divested from the club to the Treasury Department’s satisfaction, including Juan Pablo. That is not going to happen quickly. It may not happen at all.

It takes money to fund a prosperous youth system. Envigado’s has just dried up, and there’s no telling how long it will be before it returns, or if it ever will. That small threat of relegation has just gotten much larger, and that’s the least of their concerns now.

American Promotion Story

On Thursday, December 2, MLS commissioner Don Garber gave his annual State of the League speech, marking 15 years at the helm. In it, he hit upon such things as expanding the playoff field from 10 teams to 12, the goal of expanding the league to 24 teams by the end of the decade, renewing the collective bargaining agreement (set to expire January 31, but the expiration of which won’t actually affect any games until March), the desire to hold all the games on the last day of the regular season at the same time (ala most everybody else on the planet), and the desire for greater transparency in financial dealings regarding player movement.

Also touched upon, briefly, was the ever-looming question of that most international of touches, promotion and relegation. Garber was brief in his address of the topic, stating “it’s not happening anytime soon.”

Promotion and relegation is often brought up by some as something that MLS needs to at some point do if it truly wishes to be as much a member of the international soccer community as it claims. Think of the excitement towards the bottom of the table, they say. Think of the lack of having to treat clubs like movable franchises anymore, when any city in America can simply win their way into MLS! And besides, everybody else does it; let’s get with the program! Some particularly bold proponents might suggest that the other North American leagues would do well to also enact it.

These people are then quickly met with the other side of the coin, as told by the opponents of promotion/relegation. The owners bought into MLS as franchise owners and don’t want to see their investment go poof due to one bad season. The dropoff in revenue would be severe, and MLS clubs aren’t all financially healthy enough to survive it. Promotion/relegation would result in a league of haves and have-nots, much like in other leagues, where any given season begins with only a handful of clubs even able to dream of lifting the cup, and American leagues value parity.

As far as MLS is concerned, I have to agree with Garber here. MLS is growing, yes, and growing at a rather heady clip at that. But the difference between a league with teams healthy enough to sustain themselves, and a league with teams healthy enough to survive getting chucked into a minor league, is vast. With the recent death of Chivas USA, one could plausibly hesitate to say that MLS, as well as it has done, has even fully cleared the first hurdle, never mind the second. This is still a fragile product if handled improperly. Being reckless with the health of the constituent clubs could very easily spell disaster. Maybe one day MLS reaches that point where it’s safe to consider it. But that day is far from now.

As things stand, teams don’t promote or relegate in the traditional sense. Cities and teams do move up or down, but it’s done on an ad-hoc basis. If MLS sees fit to call up a lower-level team, they just do it, as has been done with, for instance, all three of the Pacific Northwest teams. If a team in lower levels wants to move up or down, they just move their team into the relevant league, as they’re not all interconnected anyway.

This does not, however, mean formal, regulated promotion and relegation can’t still be a concept put into practice in America.

MLS can’t currently handle it. The fourth-tier USL Pro Development League has been largely converted into a minor-league system for MLS clubs. But that still leaves tiers two and three, the NASL and USL-Pro respectively (even if USL-Pro is also heavily affiliated to MLS). All manner of cities looking to prove themselves worthy of joining MLS have come to these two leagues to start up a club and try their luck at impressing Don Garber. As cities get accepted, their lower-tier clubs fall away and more are started to take their place. It seems to me that if promotion and relegation is to be seen in America, a good idea would be to test it out at a sub-MLS level.

The first thing one would have to do is further cement USL-PDL as the minor league tier and find replacement affiliate teams for those MLS clubs with affiliates in USL-Pro. I don’t think that would be all that difficult in theory, though in practice it would take some level of convincing for everyone involved. Being an affiliate does offer a level of stability. But for this test to happen, those affiliations need to be cleared away. Because if promotion/relegation is what you want, what you’d probably want to do is to start by flipping teams between NASL and USL-Pro. The drop from NASL to USL-Pro would not be anywhere near as painful as the drop from MLS to NASL. If a club cannot cope with that smaller drop, an MLS team sure wouldn’t survive the bigger drop.

The attendance figures show the lower degree of decline. The average attendance at an MLS game this season has been 19,148. NASL average attendance has been 5,501. USL-Pro average attendance has been 3,114. [NOTE: This originally read 16,076 for MLS. That was the figure for the Chicago Fire, not the league. Thanks to Shawn Ferdinand for catching that.]

You do have at least some immediate buy-in here. While MLS is against promotion and relegation, NASL head Bill Peterson is in favor of it, as well as the abolition of a salary cap, another thing that would bring American soccer into line with international norms (though at great financial risk). And before NASL and USL split apart in 2009 into their current forms, promotion/relegation was in fact being bandied about as something they could do. Of course, Peterson has a swap between NASL and MLS in mind, not NASL and USL-Pro. But if he could be brought around to the idea that a successful implementation between NASL and USL-Pro could help lead to adding MLS to the mix as well, I think Peterson could deal with being the hunted as opposed to the hunter. And he does have the backing of national team coach Jurgen Klinsmann, though this could be a rather dubious accolade given Klinsmann’s propensity to pick verbal fights with just about everybody Stateside.

But that still leaves getting USL to sign on as well. And as they’re the ones affiliated to MLS at both Pro and PDL levels, it should come as little surprise that president Tim Holt has echoed Garber in saying that promotion/relegation is “some distance down the road”. He’s not completely against it, but he doesn’t look to see the point in fixing what isn’t currently broken.

Bill Peterson has some aggressive ideas regarding the future of American soccer. Perhaps those ideas might even be right, though the widening salary imbalance between teams in NASL is rather worrying. He absolutely has his share of support for his ideas. But in order to implement them any more broadly than they currently are, he’s going to need to get the other leagues to sign on. Currently, that’s what he doesn’t have.

Kickoff

The wide world of soccer news, when you look at it, isn’t really all that wide. The bulk of the attention will, naturally, focus on wherever it is the best players are. England. Italy. Spain. Germany. France. The UEFA Champions League. The World Cup. The endless transfer rumors surrounding same, the dollar figures (usually in euros). The world beyond is often only referenced when the latter stages of World Cup qualifying comes around, when a major star exits the major leagues for a paycheck or semi-retirement, when a top prospect from overseas is being courted, or when it’s the country’s domestic league. It all, eventually, comes down to western Europe, and who is considered worthy of being in western Europe but for whatever reason isn’t.

And that’s fine. If you only seek to watch soccer as a sport, there’s nothing wrong with that. And I certainly watch my share (to get it out of the way now, you are dealing with an Aston Villa supporter). But to me, part of the appeal of soccer is in its envelopment of the entire planet, not just a small subset of it. Not only do many of the world’s top players come from outside that subset, but off the field, much of the world’s culture, and its issues, and its economy, and its conflicts, in some way converge on the ball. People often like to dismiss sports as some silly aside, a distraction from the more serious issues in the world, but what is culture but that which people do as a group? There is a music culture because people create and enjoy music, and subsets within music because different people prefer different genres. There is a car culture because people enjoy cars. There are national and ethnic cultures because groups of people live in certain places, and exist as different races together. And there is one all-encompassing culture of humanity, because we all exist on Earth together. Soccer is the same way.

Let me put it this way. Think of all the times that you can in which the entire world, or at least enough of the world to get away with saying ‘the entire world’ in polite conversation, stopped in its tracks and mutually focused on the same event, at the same place, at the same moment in time. It is a safe bet that every four years, the World Cup final will qualify as just such a moment. (The Olympic Opening and Closing Ceremonies come close to this as well, but are diminished some as American broadcaster NBC tape-delays the footage.) Outside of the World Cup and Olympics, can you find moments that captures the world’s immediate, undivided attention in a similar manner at least at the same quadrennial rate? I don’t think you can.

Something that draws the attention of this much of humanity cannot help but influence, and be influenced by, much of the rest of what makes the world run. Politicians have hitched their wagons, staked their agendas, staked their infrastructures on the well-being of the national soccer program. Families have staked their livelihoods on the skill of one soccer prodigy, and hoped that the agent that has come to sign them is equally skilled, and honest, in their intent. Underworld syndicates have staked untold amounts of money on their ability to rig matches without being caught, and the players and referees they approach stake their careers on the immediate payday the syndicates give them. Smaller communities have found fame and recognition, however fleeting, when their local club does far better than the size of the community would suggest.

And vast amounts of all of this occurs far away from the glamour competitions. It is that world which I prefer to inhabit; the world of soccer that is truly global, that concerns itself with the macro rather than the micro. Edinson Cavani may go to this club, or he may go to this other club. Premier League managers may flit in and out like the tides. These matter to the involved clubs, but only really for a short time. The suffering of migrant workers building stadiums in Qatar, and the stadiums themselves, and the impact on FIFA surrounding it all, that is far more lasting. The impact of Financial Fair Play, be it on European competition, the clubs it bars from same, or simply in its abstract effectiveness, that is more lasting. The usage of artificial turf, maligned for its presence in the Women’s World Cup in Canada- starting in June- that is more lasting. And knowing all those factors that go into what you see on matchday, even matchdays in the minnows of the soccer world, will go a long way towards knowing your planet as a whole.

Thus, the tagline: To understand soccer, understand the world.

Welcome to the Minnow Tank. Enjoy your swim.